Greek Jews of Salonica

The history of the Jews of Salonica or Thessaloniki, begins in ancient Greece with the arrival of the Romaniote Jews, who came after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD. Thus, this would place them as the first of the Jewish Diaspora to settle in Greece. Two other major groups of Jews came to Salonica. These are the Ashkenazi, and finally, the Sephardic Jews. These people enriched an already thriving city with their arrival, under the Romans, the Byzantines, and later the Ottomans. Salonica would become known as the only city in the Jewish Diaspora that maintained a Jewish majority for centuries, which held up until World War II. Then, cataclysmic events unfolded that would bring about their near destruction.

The Romaniotes called themselves “Romaioi,” similar to the Byzantines, who described their roots as being from the “Roman” Empire. Though most settled in the northern Greek city of Ioannina (Yiannena), many Romaniotes called Salonica home. By the mere fact that they were living in Greece among Greeks, who were polytheistic, benefitted both groups. A harmony between these people resulted in exchanges of ideas from the polytheistic Greeks to the monotheistic Jews. In fact, the first written proof of the existence of the Romaniote Jews is Paul’s letter to the church in Salonica (Thessalonians Books 1 and 2 of the New Testament). Early Byzantine emperors were hostile to these Jews. Yet, they adopted the language and customs of the Greeks as their own, while maintaining their distinct Jewish identity.

In the late 14th century, another group of Jews, the Ashkenazi, emigrated from Bavarian Germany and Hungary, from where they were persecuted. Like the Romaniotes, they assimilated easily into the city.

The Sephardic Jews, primarily from Spain and Portugal, would be the latest, and largest group to emigrate, and are distinct from the Romaniotes and Ashkenazi. Rather than face conversion to Catholicism, imprisonment or torture, the Sephardic Jews arrived in Salonica after they were expelled under the “Alhambra Decree” of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain in 1492. These newly emigrated Jews were comprised of textile workers, artisans, and entrepreneurs, many bringing a new vitality into the city. The first printing press in the Ottoman Empire was begun by Sephardic Jews in 1494 in Constantinople and the second in Salonica. Their unique language, called “Ladino” — originally a mixture of Spanish and Hebrew, which later grew to include Arabic, Turkish, French, Italian and Greek — would become synonymous with Salonica. Since the Sephardic group prevailed in numbers, most synagogues in Salonica were built by the Sephardic population.

All three groups of Greek Jews — or better still, Jewish Greeks — settled into their new adopted land. After the Balkan Wars in 1912, the Jewish population was given full citizen rights, as equals, under the new Greek Constitution, but antisemitism still existed. After World War I especially, the influx of new Christian immigrants from Asia Minor brought both groups—Christians, and Jews—at odds with each other, competing for skilled and unskilled labor. However, in the years that led up to World War II, the new fascist government led by Ioannis Metaxas, instilled into the Jews a sense of self-identification as Greeks, who had been citizens since 1913.

These Greek Jews never ceased to affirm their sense of belonging to the Greek nation. Many served in the Greek army against the Italians in the Greco-Italian campaign. In fact, one battalion was called the “Cohen Brigade,” comprised of many Jews from Salonica who fought in front line action. Many Greek Jews were killed or wounded alongside their Christian brethren. One such soldier was Colonel Mordecai Frizis, the first high-ranking Greek officer to die in World War II. While leading his troops on horseback in Epirus, he was mortally wounded, yet, he refused to dismount. With full knowledge that he would not survive, he gave orders to his loyal followers to press the attack, giving the Greeks and the Allies their first victory.

After the German invasion and the subsequent takeover by the Axis powers, sacred scrolls of the Torah and Jewish artifacts were confiscated and sent to Germany. Jewish Greek newspapers were shut down and were replaced with antisemitic newspapers. The Grand Rabbi, Zvi Koretz, was arrested and sent to a concentration camp. All Greek Jews were forced to wear a yellow Star of David on their clothes.

Then, on July 11, 1942, the Germans ordered every Greek Jew between the ages of 18 and 45 to assemble in the main square in Salonica, where they would suffer untold humiliation in front of taunts by the Germans and germanophile, anti-semitic Greeks.

The Greek-Jewish community was slowly led into believing that they could buy their freedom. After paying this exorbitant ransom came the ultimate horrible betrayal: deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau. This came about despite strong opposition by Greek Christians and an outcry from Salonica’s leading citizens and clergy, such as Archbishop Damaskinos. The Greek puppet government, along with their germanophile leader were powerless. Instead, the Nazi-controlled newspapers incited fears and fueled more anti-semitism, threatening those who helped Greek Jews with severe punishment or death.

Despite the threats, the edicts were disregarded, even by some of the Greek police and clergy. Together with ordinary folk, they helped a few find sanctuary and escape, at the risk of their own lives. Some who did escape into the mountains fought alongside the ELAS (Greek communist) partisans, and it is estimated that one thousand Greek Jews did so. The world would come to know of the bravery of Polish Jews who died in the Warsaw ghetto, however, the armed Jewish Greek resistance is practically unknown. For some of the 13,000 Greek Jews who fought in the Greco-Italian campaign, the experience in the early years of the war would pay dividends later, as freedom fighters toward Germany’s ultimate defeat. Yitzak Mosheh and Moshe Bourlas, both Salonican Jews, escaped into the mountains and joined the ELAS partisans. Both became kapetans, or partisans leaders, and these Greek Jews called themselves “Greeks,” hoping to one day return to their homes in Salonica, or Ioannina, Agrinion, Athens … . As freedom fighters, and even in the concentration camps, Greek Jews never ceased to affirm their sense of belonging to Greece.

Sadly, Greek Jewry was virtually annihilated. Of the 57,000 Jewish-Greeks who once lived in Salonica, only 2,000 survived the war. Those who returned to Salonica found few remaining family and friends. In their once thriving community, that had existed for two thousand years, their properties had been confiscated and the Jewish cemetery was destroyed.

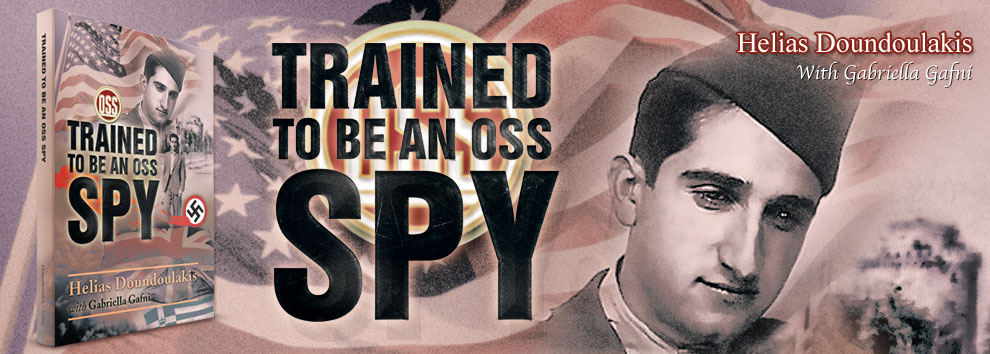

In 1944, within an abandoned Jewish Greek textile factory in Salonica, OSS agent Helias Doundoulakis operated his wireless radio that was used to send messages to Allied Headquarters in Cairo, in TRAINED TO BE AN OSS SPY.

SEE:

The United States Holocaust Museum

The Jewish Community of Thessaloniki

The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki

The Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum

Photographs courtesy of the Archives of the Jewish Museum of Athens, and Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation